As Americans prepare to partake in their annual day of football bliss, otherwise known as Super Bowl Sunday, even the most ardent NFL fans would not be able to fathom just how far this precious piece of Americana has come since its inaugural game in 1967. When the Kansas City Chiefs take on the San Francisco 49ers in Las Vegas on Sunday, February 11, it will mark the 58th installment of the big game. But when compared with how the first Super Bowl was played by the athletes and absorbed by the world, this year’s contest is unrecognizable from its unassuming debut and further demonstrates its expanding grip on today’s pop culture.

1967 vs THE PRESENT

The first glaring difference between the first game played with the NFL taking on the AFL in 1967, which pitted the Green Bay Packers against the Kansas City Chiefs, was what the event was called. The game was labeled the “AFL/NFL World Championship Game,” and the first two championships were retroactively named Super Bowls I and II after that; it was not until the third such contest in 1969 that it was referred to as the “Super Bowl.”

In 1966, NFL commissioner Pete Rozelle and the AFL’s brass were spitballing on what to call the ultimate professional football championship. One of Rozelle’s suggestions for the name of the new game was “The Big One.” That name never caught on. “Pro Bowl,” was another Rozelle idea. Had the name been adopted, there would have been confusion, for that was the name used for the NFL’s All-Star game. “World Series of Football” also died quickly, considered too imitative of baseball’s Fall Classic.

Rozelle finally decided on “The AFL-NFL World Championship Game,” but the moniker was considered clunky and never took off. It was Lamar Hunt, the main founder of the American Football League and owner of the Kansas City Chiefs, who came up with the term “Super Bowl.” According to his son, Lamar Hunt Jr., the idea came from his “Super Ball” toy.

“My dad was in an owner’s meeting. They were trying to figure out what to call the last game, the championship game. I don’t know if he had the ball with him as some reports suggest. My dad said, “Well, we need to come up with a name, something like the ‘Super Bowl.’” And then he said, “Actually, that’s not a very good name. We can come up with something better.” But “Super Bowl” stuck in the media and word of mouth.”

However, the real contrasts linking 1967 to the present are found in the simple economics surrounding all aspects of the Super Bowl, especially off the field. The amount of money spent and earned on the Super Bowl is staggering; here is a brief list of financial ways the big game has grown.

COMMERCIALS

Part of the allure for all ages and genders of investing four hours watching the Super Bowl is viewing the new commercials. Companies understand that more eyeballs will be in front of the television on this day than the other 364 opportunities during the year, so they make their chance to reach the masses count. In turn, the television companies have learned that those companies will spend a princely sum to do so.

In 1967, a 30-second spot on NBC’s broadcast of the first Super Bowl cost an average of $37,500. Businesses such as Ford, Chrysler, RCA, RJ Reynolds Tobacco, McDonald’s, and Budweiser, among others, bought air time. However, taking a look at one company’s sexist stance, one that would have no chance of being aired today, emphasizes just how different times were in the 1960s in more ways than just football.

The ad from Goodyear which aired during Super Bowl I featured a damsel in distress stranded roadside after her car’s tire blew. Because the darkness of night was no place for a single gal to linger, the woman wrapped her coat protectively tight and sought a payphone, presumably to call a burly man to get her out of the situation. Oh, how far we have come…

In comparison, a similarly timed ad for this year’s Super Bowl will cost approximately $7 million. Brands such as Oreos, Dorito’s, and M&Ms will reportedly pony up without batting an eye to secure a spot in this year’s lineup, knowing they will get the biggest bang for their buck on this day.

AVERAGE TICKET PRICE

Remarkably, the average ticket price to watch the Packers and the Chiefs in person was $12 with the cheapest seat setting one back just $6. $12 in 1967 amortizes to equal $111.88 today.

This year, to enter Allegiant Stadium, the least expensive seat found on secondary markets is $8696, and the average ticket costs $10,891.

So, when comparing apples to apples by putting in terms of equal value in today’s economy, it is roughly 97 times more expensive to enter this year’s game than it was to watch the first Super Bowl in Los Angeles.

FOOD AND BEVERAGE

There is no clear way to compare the eating and drinking habits of Americans today to those in 1967. However, based on current estimates, the amount of food and drink consumed by Americans on Super Bowl Sunday may be the best piece of evidence to prove just how glutinous United States citizens are and how huge of a social event the game has become.

According to statistics gathered by Premio Foods, Super Bowl Sunday is the second-largest food holiday, only trailing Thanksgiving. An estimated 1.25 billion chicken wings will be ingested on game day alone. To wash that down, Americans will guzzle down an estimated 325.5 million gallons of beer (enough to fill an Olympic-sized pool 2,000 times) and $2.37 million worth of soda products.

FIVE PECULIAR ITEMS YOU MAY NOT KNOW ABOUT SUPER BOWL I

If the aforementioned statistics surrounding the Super Bowl and how it transformed its viewing public’s behavior sound amazingly outlandish, there are aspects of the game itself that would seem ridiculous and impossible for football fans to fathom today. Here is a brief collection of quirky and eccentric facts from Super Bowl I, which was played on January 15, 1967:

The L.A. Coliseum was only two-thirds full for the game. Super Bowl I was not a sellout; it wasn’t even close. 61,946 people turned the turnstiles, leaving the 94,000-seat Los Angeles Coliseum roughly one-third empty. Remarkably, a regular season game a month earlier between the Packers and the Los Angeles Rams drew more than 72,000 fans. The main reason? Fans thought the ticket prices were too high.

15 million people were not allowed to watch the game on television.

Unbelievably, Super Bowl I was not televised to those within a 75-mile radius of the Los Angeles Coliseum in adherence to the league’s blackout policy. Back in 1967, the National Football League blacked out every game in the local market, convinced that televising the game locally would cause fans to watch on TV rather than pay for tickets. The league refused to make an exception for the Super Bowl, and this decision affected over 15 million people in Southern California.“The game,” one columnist wrote, “has not yet caught on with the local populace.”

The location was not picked until six weeks before the game.

Nowadays, Super Bowl sites are selected years in advance; the next three locations after this year have already been determined. However, the decision to play the first Super Bowl in Los Angeles was not made until December 1st, just six weeks before the game was to be played.

In November, several cities were still in the running to host the game. NFL Commissioner Pete Rozelle identified the Coliseum, along with Miami’s Orange Bowl, Houston’s Astrodome, and the Sugar Bowl in New Orleans, as potential sites.

Cleveland Browns owner Art Modell quickly endorsed the idea of playing the game — some dubbed it the World Series of Football — at the Coliseum or Rose Bowl. L.A. had the temperate climate and population base the leagues wanted.

The game was covered by two different networks.

Both CBS, which held the rights to broadcast NFL games, and NBC, which aired AFL games, paid $1 million for the rights to televise the first Super Bowl. While CBS produced the feed of the game, each network employed its own broadcast crews. The two networks fought for ratings points as furiously as the two teams on the field, and it remains the only joint broadcast in Super Bowl history.

In fact, because of the rivalry between the two networks, the integrity of the game was compromised. The Packers kicked off to the Chiefs to begin the second half, but only those watching on CBS saw it. Because NBC’s halftime interview with Bob Hope ran long, they were late coming back from a commercial break. The referees blew the kickoff return dead before it happened, and, despite the arguments from Packers’ coach Vince Lombardi, Green Bay was forced to perform a “do-over” and kick off a second time.

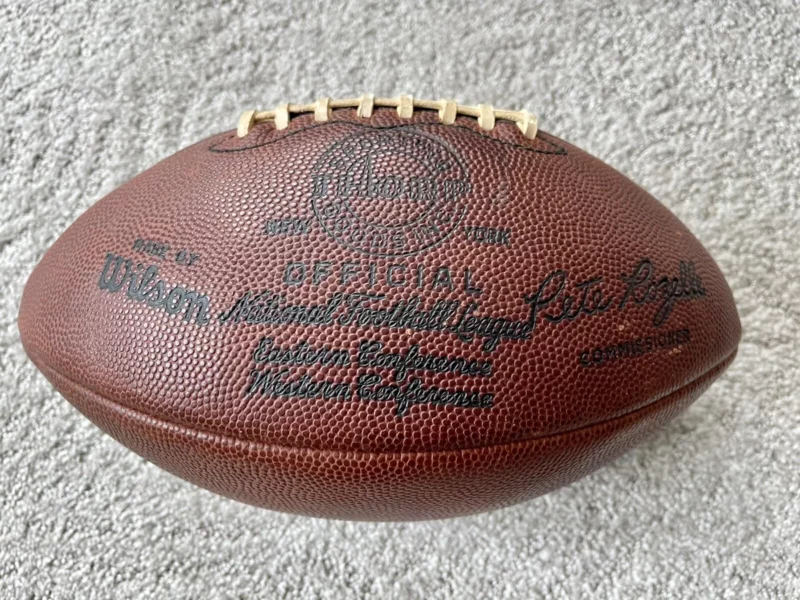

The Chiefs and Packers used two different types of footballs.

The NFL and AFL used different footballs during their seasons, so the Packers and Chiefs used different balls in the Super Bowl. When on offense, the Packers played with the official NFL ball, “The Duke” by Wilson. When possession switched to the Chiefs, they used Spalding’s J5-V, which was easier to pass because it was slightly skinnier and longer.

This separate ball rule continued through the first four Super Bowls. It wasn’t until the official merger of the two leagues in 1970 that a uniform ball was used, and the Wilson ball was adopted as the new official ball of the NFL.

SUPER BOWL SUNDAY: ONCE AN EXPERIMENT, NOW AN AMERICAN TREASURE

From sea to shining sea, and over 130 countries worldwide, the last NFL game of the season has become must-watch viewing; of the 30 most viewed events in the history of television, 22 are Super Bowls. With the ever-growing stranglehold the NFL enjoys in popularity over other major sports, that trend is not ebbing anytime soon. However, those pioneers who devised the championship professional football game could not have envisioned the spectacle into which it has grown.