Off coverage. The very phrase seems to conjure up negative connotations in the minds of Packers fans. I think many remember the “bend but don’t break” philosophy adopted by the Pettine defenses of the last few years – which tended to lead to both bending and breaking. To many, the idea of off coverage seems synonymous with passivity. Whenever a short-yardage situation comes up, off coverage is seen as a white flag from the defense.

Over the past few weeks, this view has come up several times. I especially noticed the discussion ramp up following the narrow Week 16 victory over the Browns. The Packers defense was coming off of a disappointing two-week performance. In Week 15, they had allowed 30 points to Tyler Huntley, a backup QB for the Ravens. Against Cleveland the following week, they surrendered over 400 yards to Baker Mayfield and the Browns running attack. I’ve outlined a few factors, both in opponent scheme and individual matchups, that contributed to those poor defensive performances.

When I’ve watched the All-22 this season, I’ve never really noticed consistent issues with too much soft coverage. Even in those games where the defense struggled, the troubles seemed to be rooted in other issues. However, it’s hard to take in everything on only one or two viewings, so I went back and rewatched a number of games. I wanted to get a wide range of opponents, so I picked games from both the defense’s most successful strectch and from times where they’ve struggled. Specifically, I watched the games against the Cardinals, Chiefs, Seahawks, Rams, Browns, and the second game against the Bears. In the course of my rewatch, I discovered some interesting things.

Busting a Myth

Before we get into my findings, though, I want to address what I believe is a common misconception about off coverage. As I mentioned, I often see people decrying off coverage on short-yardage situations. The idea seems to be that it is impossible to defend short routes – such as slants, outs, stick routes, and short curls – from off alignments. I don’t believe this is true. In fact, I think that playing in off coverage can actually be beneficial in defending short routes, depending on the skillset and athletic profile of the defender. Just take a look at the following cut up. Clip #1 is our old friend Rasul Douglas getting a PBU against a slant on 3rd & short during his time with the Panthers. Clip #2 is a Seahawks CB knocking the ball away against Allen Lazard on 4th & short. Finally, Clip #3 features Chandon Sullivan and Henry Black defending slant routes from depth.

Just as playing off coverage doesn’t necessarily mean surrendering short routes, playing close to the line isn’t always effective in defending these same quick-game concepts.

What I Found Watching the Film

Before I get into what I found, let me be clear. The Packers do play a lot of off coverage. I think there are multiple factors that lead to this coverage tendency. However, as we have seen from the previous section, off coverage does not necessarily mean passive coverage.

Scheme

First, many of the coverages played by the Packers often entail the CBs playing from depth. I don’t have exact numbers, but from observation the two most common coverages that the Packers play appear to be Quarters (4 deep zones, 3 underneath zones) and Cover 3 (3 deep zones, 4 underneath zones). Both of these coverages entail the outside corners playing deep zones; in Quarters, the two safeties play the other two deep zones, while in Cover 3 one of the safeties “spins” down into the box. Furthermore, the Packers typically play “pattern-matching” versions of these coverages. This means that these zones can change based on the route concept that the opposing offense is running.

Examples from Quarters Coverage

Let me give some examples of how these factors can lead to more off coverage. In the Packers’ Quarters coverage, one of the 3 underneath defenders is often a slot CB. This slot CB – usually Sullivan – has to follow a variety of rules depending on the offense’s actions. I won’t go through all of them, but to summarize, the slot CB generally has to play man-to-man on flat routes, reroute vertical routes from the slot, and pass off shallow inside routes to the interior. For reference, most rules I’ve seen define “shallow” as less than 5 yards from the line of scrimmage. In order to maintain proper leverage and angles in these situations, the slot defender – also called an apex or nickel (Ni) defender – benefits in playing from depth.

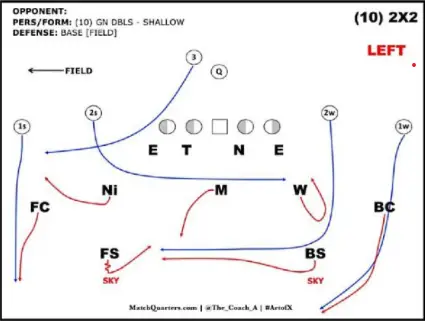

Another important aspects of Quarters is the way the deep zones operate. To quote Cody Alexander’s fantastic book Match Quarters, “In each coverage, there will be a low, intermediate, and ‘cap’ player . . . [in Quarters] the Ni has low, [safety] intermediate, and the CB is the cap.” Unlike some other two-high coverages, the safeties are more aggressive in Quarters, getting involved in run support and “robbing” intermediate routes. This means that the outside corners have to “cap” (stay on top of) vertical routes like posts. This is illustrated in a diagram from Alexander’s aforementioned book. The field safety (FS) and boundary safety (BS) can play down on intermediate routes, while the field corner (FC) and boundary corner (BC) cap the deep routes.

Cover 3 has some similar factors. The outside corners have less safety help than in some other coverages, so they have to guard against vertical routes. Both coverages put the defense in a good position to deal with some of the offensive trends that have been sweeping the NFL. Getting the safeties playing downhill allows GB to better defend intermediate routes – an important part of the popular Shanahan/LaFleur/McVay play-action offenses. In these coverages, the safeties are also more involved in fitting the run; this frees slot defenders from major run responsibilities, removing conflict and allowing them to play the pass on RPOs.

Rub Routes

Another schematic reason behind the GB tendency to play off coverage is the danger of “rub” or “pick” concepts – in other words, route distributions that place defenders in danger of being blocked from the zone or man that they need to cover. This has factored in a lot when the Packers face teams like the Browns and Rams that frequently use condensed formations. Whenever a receiver gets closer to the core of the formation, space gets constricted and the possibility of a rub or pick increases. Playing off coverage can counteract this effect. A lot of rub routes attack man coverage, such as the Mesh concept (Dusty Evely has a great video on that here), but zone coverages can be affected as well.

Here’s a great example from the Rams game. Take a look at the route concept to the bottom of the screen. The Rams are running a Curl/Flat concept against Green Bay’s Quarters coverage. The #1 receiver runs a Curl route, and the #2 receiver runs the Flat route. You’ll notice that both CBs on that side (Stokes and Sullivan) are lined up off the line and at staggered depths, which allows Sullivan to flow freely to the flat with the route from #2. If one or both of the CBs were in press, then the vertical stem from #1 would have hindered Sullivan’s ability to travel to the flat with #2. Unfortunately, Stokes can’t trigger fast enough to prevent the completion to the Curl (more on that in the next section).

Personnel Capabilities

Finally, I think that the different skillsets of Green Bay’s CBs influence their alignment. This was one of the most interesting things I noticed during my rewatch. When I reviewed the Cardinals game, I noticed that in most situations both Stokes and Douglas were playing off. The Chiefs game was similar, though Stokes was out with an injury. However, during the Seahawks game, their deployment shifted. In certain situations – usually when the opposing offense was in shotgun formations – Stokes would get into a press man position while Douglas stayed in off coverage.

This adjustment fascinated me. My theory is that up until the Seahawks game, the defensive staff was still figuring out the best way for Stokes and Douglas to succeed as a tandem. Whether the change was rooted in self-scouting by the pair or was initiated by the coaching staff is hard to say. The point is, after the Seahawks game Stokes and Douglas would continue to play in those respective alignments whenever opposing offenses were in shotgun.

What Prompted the Change?

As I said, from the outside it is hard to identify who initiated the change. However, I believe that the adjustment came as the respective skillset of the duo became more apparent. From what I have seen of his film, Stokes is much more comfortable mirroring receivers from a press position. He struggles to keep his footwork clean when reading routes from off coverage. You can see this in the clip I posted above, where he gets too much weight on his back foot and has to double-step before breaking on the catch point. This next clip is also illuminating. Stokes, at the top of the screen, gets off-balance and choppy with his footwork while trying to play the double move. Compare that to the control that Douglas shows to the bottom of the screen.

Moreover, Stokes’ ability to read the QB and identify where the ball is going don’t seem to be up to par at this point. Check out the difference in these two clips. In the first, Rasul is quick to identify the WR screen and trigger down to stop it. He begins moving almost as soon as Murray begins his throwing motion. Stokes, in the second clip, doesn’t begin to break on the ball until it is nearly at the WR.

Given these limitations in off coverage, Stokes began to take a press position more often. As this next cutup shows, he appears to be able to operate much more smoothly and comfortably there, and his speed allows him to still guard deep routes.

Douglas shows a much greater ability than Stokes to read and react to routes from off coverage. He’s more balanced in his body control and footwork. These traits, combined with his short area explosiveness, allow him to play off coverage effectively.

A Note on Chandon Sullivan

I was primarily focused on the outside CBs for this article. However, during my film review I did pay attention to Chandon Sullivan’s alignment tendencies and strengths. I think that, like Douglas, he is best suited to playing from depth – though he doesn’t have the high-level change-of-direction that Rasul does. In press, he can struggle to keep up with shiftier route-runners, as in this clip where he faces Jarvis Landry.

Is There More to This Adjustment?

As I was considering the advantages of this alignment, I began to develop a theory. Putting Stokes in press while keeping Douglas in off coverage fits their skillsets well. However, I suspect that there is more to it. I think that the GB defense is trying to “trap” the opposing offense.

From a quarterback’s point of view, which side would you rather throw to? The side where your receiver is being pressed at the line and is at risk of having his route or timing disrupted, or the side where the CB is playing 7 yards off? You’re probably going to be influenced to throw to the off coverage side.

Unfortunately for the offense, well-played off coverage can (just like press coverage) force a perfect throw. And, if you don’t make a perfect throw against Rasul Douglas? Well then . . .

Now, to be fair, I have no way of confirming this theory. Whether or not the defensive staff developed this alignment in part to influence offensive decisions is impossible to say without being inside the building. It may just be a way to leverage the respective skillsets of the CBs.

Whether or not it was purposeful, I’m a big fan of the effect that this type of alignment has. In such an offensive-oriented league, defenses have to find ways to dictate what an offense can do, even to a small degree. I believe that the mix of off- and press-coverage allows the Packers to do this.

A Side Note About the Browns Game

As I mentioned, criticism over “soft” off coverage seemed to ramp up following the game against the Browns, so this game was one I especially focused on in my rewatch. Playing “soft” can, admittedly, be subjective. However, I didn’t see a greater degree of passive coverage in that game compared to other games that I watched – including the shutout against the Seahawks. They followed the same general tendencies that they had in previous games, including the alignment vs. shotgun that I described in the previous section.

Personally, I think that the defensive issues that we saw in the Browns game had more to do with the Cleveland run game than the passing game. Despite this, I did want to address several snaps that others have pointed to as examples of “passive” coverage during the matchup.

The First Play

To start out, we have the Packers in Cover 1 (man coverage with one deep safety) in the redzone. The Browns came out in a 12 personnel set (1 RB, 2 TEs). In order to counteract a possible run, the Packers are in their base 3-4 defense. The Browns spread out into empty. Instead of choosing to drop an outside linebacker or defensive lineman into coverage, the Packers opt to rush 5. This leaves 2 defenders (Stokes and Amos) in man coverage with no deep help on the 2 receiver side of the formation, and the #2 receiver is able to run a slant for a nice gain.

At first, it appears as if the defense is just surrendering an easy completion by playing off coverage. With hindsight, it’s easy to say that Stokes should have been pressed on the point man in the bunch. However, look at the situation from the defense’s point of view. Anytime they see a receiver bunch, they have to be alert for the possibility of a rub route. One such concept in this situation might be an underneath route from #1 and a vertical stem – such as on a Dig or Corner – from #2. The vertical stem from #2 would block Amos from travelling with the underneath route from #1.

This problem might be addressed by calling a different coverage, but Cover 1 makes sense against 12 personnel. It allows the defense to get more bodies in the box against a run.

The Second Play

The second play I want to highlight also takes place in the red zone. The Packers are in Cover 1 from their “Penny” Nickel package. This package keeps 3 DL on the field while substituting the slot CB for one of the inside linebackers. The Browns are in empty, and run a type of downfield rub route on the two-receiver side. The #2 receiver runs a corner route, getting in Douglas’ way as he tries to trigger on the underneath route from #1. Sullivan has his eyes on #1 and recognizes the pattern late.

Again, playing off makes sense from a defensive perspective here. Corner routes and “Scissors” concepts (Corner from #2 and Post from #1) are a distinct danger in the red zone. In fact, the Packers struggled against Scissors several times early in the year. The CBs have to be able to stay on top of these routes since they don’t have deep help in this situation. I think the primary issue in this situation is Sullivan’s slow trigger on the underneath route; he appears to have trouble stopping his backwards momentum.

Conclusion

Though fans may prefer otherwise, I think that the Packers have some good reasons when they play in off coverage. Some of it is dictated by their scheme or the formations of their opponents. Other times, it is a way to put their CBs in a position to succeed. Ultimately, off coverage is simply a defensive tool, just like press coverage is. Different situations require different solutions. Hopefully I’ve helped illuminate why we’ve seen the Packers use off coverage frequently throughout the season.

Follow me on Twitter at @Sam_DHolman. To read more of our articles and keep up to date on the latest in Wisconsin sports, click here.